For the first time, scientists have witnessed fragments of fractured metal fuse together without any human intervention, in a process that has overturned basic scientific theories. This newly discovered phenomenon, if harnessed, could lead to an engineering revolution: self-healing engines, bridges and aircraft that could reverse damage from wear and tear, making them safer and more durable.

On July 19, a joint research team from Sandia National Laboratories and Texas A&M University described the discovery in Nature.

"It was absolutely stunning to see it all in person," said Brad Boyce, a materials scientist at Sandia National Laboratories. "We've shown that metals have their own intrinsic, natural ability to heal themselves, at least in the case of nanoscale fatigue damage."

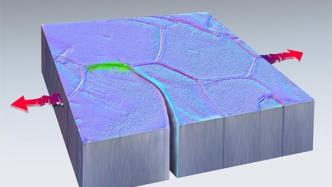

Fatigue damage is one way a machine wears out and eventually breaks down. Repeated stress or movement leads to the formation of microscopic cracks. Over time, these cracks grow and spread until they break.

The vanishing cracks that Boyce's team saw were tiny but important cracks measured in nanometers.

"From solder joints in electronic devices to car engines to bridges, these structures often fail unpredictably due to cyclic loading, causing cracks to develop and eventually break," Boyce said. "When failures occur, we must face the cost and time lost of replacement, and in some cases, even loss of life. The economic impact of these failures in the United States is measured in hundreds of billions of dollars annually."

While scientists have created a few self-healing materials—mainly plastics—the concept of self-healing metals remains largely the stuff of science fiction.

"Metal cracks just grow bigger, not smaller. Even some of the basic equations we use to describe crack growth rule out this possibility of self-healing," Boyce said.

In 2013, Michael Demkowicz, then an assistant professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and now a professor at Texas A&M University, began to study traditional material theory. He published a new theory, based on computer simulations, that under certain conditions metals should be able to repair cracks formed by wear.

The Center for Integrated Nanotechnology, run jointly by Sandia National Laboratories and Los Alamos National Laboratory, stumbled upon Demkowicz's theory.

Khalid Hattar, now an associate professor at the University of Tennessee, and Chris Barr, now with the Department of Energy's Office of Nuclear Energy, made the discovery while working at Sandia National Laboratories. At the time, they simply wanted to assess how cracks formed and propagated in nanoscale platinum flakes using a specialized electron microscopy technique they had developed that repeatedly tugs on the metal ends 200 times per second.

Surprisingly, the damage was reversed about 40 minutes after the experiment began. The ends of the crack have fused together, as if retracing the original path, leaving no trace of damage. Over time, the cracks re-grow in different directions. Hattar called this an "unprecedented phenomenon".

"Of course, I'm happy to hear that," Demkowicz said. The professor then recreated the experiment on a computer model, confirming that what was seen at Sandia was consistent with the theory he had proposed years earlier.

There are still many unknowns about the metal self-healing process, including whether it will become a practical tool in manufacturing.

"How general these findings are is likely to be a subject of extensive study," Boyce said. "We showed this happening in nanoscale metals in a vacuum, but don't know if it's happening in regular metals in air."

However, despite all the unknowns, the discovery is still a leap forward at the frontier of materials science.

"I hope this discovery will lead materials researchers to realize that, under the right circumstances, materials can do things that were never expected before," Demkowicz said.

(Original title "Scientists discover for the first time that metal cracks can repair themselves")

Related paper information:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06223-0