Black holes can obtain energy by "snacking," but the food they choose is quite different from what we eat. An analysis published in Nature Astronomy on November 4 shows that when a black hole devoured a star with at least 30 times the mass of the Sun, it emitted the brightest light ever detected in a black hole—a "fireworks display" with a peak brightness more than 10 trillion times brighter than the Sun.

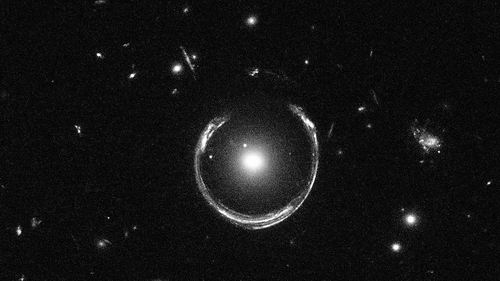

A black hole slowly devours a star, emitting a dazzling light. Image credit: Caltech

When astronomers first observed this object in 2018, they didn't realize it was a supermassive black hole flare. After noticing its increased brightness, researchers immediately aimed it at the 200-inch Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory in the United States. However, the object's luminosity curve was disappointing. "It doesn't seem as interesting as we expected," said Matthew Graham of Caltech, one of the paper's authors.

However, in 2023, the research team noticed that even five years later, the black hole flare remained exceptionally bright. They then conducted further observations using the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. The results showed that the object was approximately 10 billion light-years from Earth. To appear so bright at such a distance, the light it emitted must have been extremely dazzling. Astronomers say that this black hole flare was 30 times brighter than any black hole flare previously detected.

Researchers analyzed several possible causes for this flare. It could have been a supernova explosion near the black hole, or it could simply be a light trick—appearing much brighter than it actually was due to gravitational distortion. However, the research team ultimately found that neither of these explanations matched the observations.

Researchers believe a more plausible explanation is that a massive star met its doom when it got too close to the black hole. When the black hole's gravity tore the star apart, it emitted 40 times more light than before. They also believe that the star may not have been completely swallowed by the black hole because the flare has not yet completely dissipated.

Astronomers will continue to observe the star's demise. Joseph Michail of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics wants to know whether the jets gradually dim or erupt again when the light reaches the surrounding gas and dust. He believes future sky surveys may soon reveal more similar phenomena. "These events are likely to become the norm," Michail said.

Graham believes that astronomers will need to continue monitoring the skies to fully understand these mysterious flare phenomena. Because this black hole is so far from our solar system, it takes approximately seven Earth years to observe two years of its activity, meaning astronomers can only witness the entire process of a black hole devouring a star at about a quarter of its current rate. Graham says that comprehensively observing more such events "will be a long process."

Related paper information: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02699-0